J’ai fait une petite promenade

à côté de la rue

car c’est où

on peut regarder le monde

pendant qu’il passe

J’ai fait une petite promenade

à côté de la rue

car c’est où

on peut regarder le monde

pendant qu’il passe

Au travail aujourd’hui, une cliente s’est approché de ma caisse poussant un chariot plein de courses. Parmi les courses, il y avait une aubergine qui avait une déformation. Normalement, les clients ne veulent pas acheter des produits avec des déformations, mais cette femme a donné une chance à l’aubergine. Voici une photo :

Mon amie m’a dit que ça ressemblait à Skeeter de l’émission (dessin animé) « Doug » :

Qu’en pensez-vous ? Achèteriez-vous du produit comme ça ? Si vous avez eu des expériences similaires, racontez-en dans un commentaire. 🙂

(S’il vous plaît, n’hésitez pas à corriger mes erreurs. Je voudrais bien à améliorer mon français.)

Bonjour… C’est moi… Je me demandais si, après tous ces ans, vous souhaitez rencontrer…

Bonjour… C’est moi… Je me demandais si, après tous ces ans, vous souhaitez rencontrer…

😀 Hello. It’s been a while! I’ve been meaning to post for months now, but I’m working on what will be my very first entry written completely in French. I don’t work on it every day, so it’s taking me longer than it probably should. It’ll be coming soon.

In the meantime, I’ve taken my love and passion for language and delved into the whimsical world of YouTube. I’ve decided to begin recording my journey to French fluency, as a way to benefit myself as a means of practice, as well as to hopefully benefit new or prospective learners. That said, I posted my first (language-related) video a couple of days ago. Follow along and learn how to count from 1 to 100 en français ! The way numbers operate in French is very interesting, and although basic, has been something I’ve struggled with in the past. I recorded this video to serve as a refresher for myself, and maybe it can even help you, too. 🙂

Watch here:

Let me know what you think, either below, or in a YouTube comment.

Stay happy. See you soon.

Salut! Ça fait longtemps, mais je suis là.

Hello! It’s been a long time, but here I am. I’m happy to announce that my French studies have been going very well! When I’m learning, I can’t move on to something new until I fully understand the why and how of what’s in front of me. I take great pleasure in being completely confident in my ability to properly use a new word, as well as understanding why, when, and how to use said new word. Having said that, certain things I once had trouble with in my French studies have lately seemed to just click, and I’ve begun to understand more clearly and add to my cache of knowledge on the subject. So today, we’re going to take a deeper look at one of the first verbs beginner French speakers learn, and that’s avoir, which means to have. It’s the verb with the most conjugations, as it has a multitude of uses.

Present tense conjugations of avoir are commonplace in the beginning and are easy to recognize:

J’ai – I have

Tu as – you have (informal)

Vous avez – you have (formal)

Il/elle a – he/it/she has

Nous avons – we have

Ils/elles ont – they have

Now comes the tricky part. Avoir has numerous tenses and conjugations, depending on the mood and who’s speaking. But if you’re like me, it’s difficult to remember all the different tenses and what each one means. There’s present, present perfect, imperfect, future, future perfect, pluperfect, nearly perfect, less than perfect… Okay, so maybe those last two I made up. But the six tenses prior are all legitimate. But again, I never remember what exactly ‘present perfect’ or ‘pluperfect’ mean, and honestly, I can’t be bothered to care. So that’s why I’m taking the liberty of conjugating avoir for you in each of these tenses, as well as writing the English equivalent. This way, if you’re having trouble knowing when to use which conjugation, just remember that how you’d say it in English, that’s the translation you’d need to use in French, too. Note that as I conjugated the present tense above, it will not appear below. Enjoy.

Present Perfect Tense (English: have had)

J’ai eu – I have had

Tu as eu – you have had (informal)

Vous avez eu – you have had (formal)

Il/elle a eu – he/it/she has had

Nous avons eu – we have had

Ils/elles ont eu – they have had

Imperfect Tense (English: had)

J’avais – I had

Tu avais – you had (informal)

Vous aviez – you had (formal)

Il/elle avait – he/it/she had

Nous avions – we had

Ils/elles avaient – they had

Pluperfect Tense (English: had had)

J’avais eu – I had had

Tu avais eu – you had had (informal)

Vous aviez eu – you had had (formal)

Il/elle avait eu – he/it/she had had

Nous avions eu – we had had

Ils/elles avaient eu – they had had

Future Tense (English: will have)

J’aurai – I will have

Tu auras – you will have (informal)

Vous aurez – you will have (formal)

Il/elle aura – he/it/she will have

Nous aurons – we will have

Ils/elles auront – they will have

Future Perfect Tense (English: will have had)

J’aurai eu – I will have had

Tu auras eu – you will have had (informal)

Vous aurez eu – you will have had (formal)

Il/elle aura eu – he/it/she will have had

Nous aurons eu – we will have had

Ils/elles auront eu – they will have had

Conditional Present Mood (English: would have)

J’aurais – I would have

Tu aurais – you would have (informal)

Vous auriez – you would have (formal)

Il/elle aurait – he/it/she would have

Nous aurions – we would have

Ils/elles auraient – they would have

Conditional Past Mood (English: would have had)

J’aurais eu – I would have had

Tu aurais eu – you would have had (informal)

Vous auriez eu – you would have had (formal)

Il/elle aurait eu – he/it/she would have had

Nous aurions eu – we would have had

Ils/elles auraient eu – they would have had

The spellings of each conjugation are important, as the accidental omission or addition of a letter could potentially be the wrong translation. But getting the hang of that will come in time. And just when you thought that the previously listed eight moods were overwhelming, they don’t stop there. There are three other tenses: the subjunctive (uncertainty of events), the imperative (a demand/request/suggestion), and the three participles (perfect: having done/had; past: when avoir acts as a helping verb; present: to be in the process of). But I’ll elaborate more on those in a future post, once I get the hang of them myself. In the meantime, I hope this post has helped to clear up any confusion you may have had surrounding the enigmatic avoir. Any questions or concerns? As always, feel free to leave them in the comments below and I’ll do my best to answer them all. Also, a disclaimer: I am still learning, so if any of the above information is incorrect, please, by all means, let me know. I don’t want to be teaching potential/beginner French speakers how to conjugate incorrectly! Ce ne serait pas bon. 🙂

Happy tensing! (See what I did there?)

French is a beautiful language; from the intonation, to the flow of sentences, to the rolled rs. But if you’re not a native speaker, you may find certain rules of the language difficult to comprehend or remember. For example, in French, there can be no imprecision. What I mean is that essentially, everything must be accounted for and there should be no ambiguity in sentence structure. Still confused? I was, too, when I first began studying. But if you take a closer look, it’s not as confusing as you may think. In fact, as far as pronouns go, there are a number of different demonstrative pronouns to be used for varying occasions. I realize that probably doesn’t help at all. Which is why, for my own sake and now, hopefully, for yours, I’ve taken the liberty to give a rundown of each demonstrative pronoun. The following is a list of each, including their translations and uses.

The word ce is a pronoun meaning ‘this’ or ‘it.’ Most commonly, it’s used before the verb être, meaning to be, in the contraction c’est (this/it is). But it can stand alone.

Ce cheval mange. (This horse is eating.)

C’est bon. (This is good.)

Cet homme est grand. (This man is tall.)

Did you catch what I did there? That last one isn’t ce, but cet. But it shares the same meaning of ‘this/that.’ The difference is that ce is placed before a singular, masculine noun that begins with a consonant. And though homme begins with a consonant, hs are not pronounced in French, and therefore a t must be added to the end of ce, so that it flows better. (The same applies before words beginning with vowels.)

On the other hand, if the noun is singular but feminine, the pronoun becomes cette.

Cette femme boit. (This woman is drinking.)

Cette pomme est rouge. (That apple is red.)

Cette maison est large. (This house is large.)

Despite the gender, if the noun that follows is plural, the pronoun becomes ces, to mean these/those.

Ces rues sont longues. (These streets are long.)

Ces oranges sont bleues. (These oranges are blue.)

Ces garçons boivent du lait. (These boys are drinking milk.)

Now that we’ve covered what comes before a noun, what happens if the noun is unspecified? Ceci and cela become both direct and indirect objects in this case (providing the verb être is absent immediately afterward).

To refer to something close by, you’d use ceci. The word ici means here, and we’ve already discussed that ce means this. So essentially, this is a contraction of ce + ici, to mean this (thing) here.

Conversely, to refer to something a little farther away, the pronoun cela* is used. The word là means there, and so again this is a contraction, combining ce + là (and dropping the accent), to mean that (thing) there.

Ceci peut être difficile. (This could be difficult.)

S’il vous plait, donnez-moi cela. (Please, give me that.)

*Note that cela can also be used to mean this as opposed to strictly that. The French prefer to use cela most often, in fact, especially verbally. Ceci is rarely used unless specifically to distinguish between ‘this’ and ‘that.’

It’s better to be more specific when speaking formally. But if you’re more familiar with your listener (or reader if you’re writing in French), ça is the informal replacement for both ceci and cela, and can also mean it.

Il n’y a rien comme ça. (There is nothing like it.)

Je ne veux pas ça, je veux ça. (I don’t want this, I want that.)

Next, let’s take a look at pronoun usage when making a comparison.

If you want to reference this/that one, you’d need to use celui or celle. In French, demonstrative pronouns must agree in gender and number with what they’re referring to. Therefore, celui refers to something previously mentioned that’s masculine and singular, and celle to something that’s feminine and singular.

Quelle cravate veux-tu porter, celle-ci ou celle-là? (Which tie do you want to wear, this one or that one?)

You’ll notice that I added the suffixes –ci and –là to the end of celle. This is because celle and celui cannot stand alone, and adding a suffix is one of a few ways to make the sentence grammatically correct. Again, adding –ci (here) references something a little closer, while adding –là (there) references something a little farther.

Celui and celle may also be followed by de (of), which is used to show origin or possession, and eliminates the need for a suffix.

Dont le bateau est-ce? Il est celui de mon grand-père. (Whose boat is this? It is my grandfather’s.)

In the above construction, the second sentence literally translates to it is the one of my grandfather. In this case, celui (and celle if I’d used a feminine noun) means the one (of).

The same rules apply for plural nouns as well. The plural counterpart to celui is ceux, and the plural counterpart to celle is celles. Easy enough, right?

Quelles robes veux-tu acheter, celles-ci ou celles-là? (Which dresses do you want to buy, these ones or those ones?)

Ces manteaux sont ceux de mon fils. (These coats are my son’s.)

To wrap things up, let’s summarize:

Ce = this (before noun)

Ceci = this/that (no noun necessary)

Cela = this/that (no noun necessary)

Ça = this/that/it (informal replacement of ceci/cela)

Celui = this one/that one/the one (masculine, singular)

Celle = this one/that one/the one (feminine, singular)

Ceux = these ones/those ones/the ones (masculine, plural)

Celles = these ones/those ones/the ones (feminine, plural)

I understand this can be a lot to take in and memorize. It certainly was for me in the beginning and still proves to be sometimes. But the more you study, and the more frequently you put these pronouns to use, the easier it will become to remember when to use which one.

I hope you’ve found this informative and/or helpful! Questions? Feel free to ask away in the comments and I’ll answer to the best of my ability. Comments/concerns? Please, by all means, don’t hesitate to leave those in the comments as well. Is any of this information incorrect? I’d love to know; I’m a native English speaker who’s merely on the road to French fluency. I’m still learning and want to pass on what I know, but of course I want to be as accurate as possible. 🙂

I saw you at a time

when the wind wasn’t blowing in my direction

and you disappeared quicker

than I can say

‘Sunday’

Je t’ai vu à un moment

quand le vent ne souffle pas dans ma direction

et tu as disparu plus vite

que je peux dire

‘dimanche’

In my French studies, I’ve come across several different accents above varying letters. Par exemple: à (e.g. là – ‘there’), ô (e.g. tôt – ‘soon’), é (e.g. légère – ‘light’), and so on. Though I’ve been able to pick up on how to pronounce each accented letter due to repetitive use, I’ve still been curious as to the meaning behind each accent. It varies per language, but what (hopefully) follows is a clarification regarding each accent and its respective rules in the French language.  The grave accent, seen above the letter a in the French word là, generally marks the openness of a vowel. The openness refers to the height at which your jaw is positioned during pronunciation. (‘Open’ means your jaw is literally more open; ‘close’ means the opposite.) In French, it is used on three letters: a, e, and u.

The grave accent, seen above the letter a in the French word là, generally marks the openness of a vowel. The openness refers to the height at which your jaw is positioned during pronunciation. (‘Open’ means your jaw is literally more open; ‘close’ means the opposite.) In French, it is used on three letters: a, e, and u.

Its only purpose for appearing above letters a and u is to differentiate between homonyms that are otherwise spelled the same way; the pronunciation is not affected. In other words: a is the third-person singular present tense conjugation of the verb avoir (to have – elle a = she has). À on the other hand means to/belonging to/towards. Both words are pronounced the same; the grave accent is used to distinguish them.

When placed above the letter e, it marks a change in pronunciation. The letter è in French is pronounced open, as I mentioned earlier; it shares the same pronunciation as the ai in the English word air.

The circumflex accent plays an interesting role in the French language. When placed over the letter e (ergo, ê), it is pronounced open, much like è. I like to say that ê is pronounced the same as in the English word get when followed by the letter t; i.e. fête (party), tête (head). When used as ô, it is pronounced close, as it is in l’eau (the water), and plutôt (rather).

Not unlike the grave accent, the circumflex is also used to distinguish homophones. For instance; cote, meaning mark or level, and côte, meaning rib or coast. Now comes the interesting part.

The circumflex accent is also used to denote an English-to-French translation in which the letter s, used in the corresponding English word, has been omitted and thus is no longer pronounced in the French equivalent. Confused? Here are some examples:

You’ll notice the s was lost in translation. See what I did there?

Fait intéressant: In handwritten French, such as when taking notes, an m̂ may be used as an informal abbreviation to mean même (same).

The acute accent in most Romance languages implies a stressed vowel; i.e. a vowel that emphasis is placed on in pronunciation. However, stress is not implied by the acute accent in French. It is only used on é, and should be pronounced like the letter e is in the English word seen. E in French without the acute accent is normally stressless, and by itself, should be pronounced as the u in the English word put.

The cedilla is easily recognizable as the little tail that hangs off the letter c in the commonly used French word ça, meaning it. It is used to mark the soft s sound with which to pronounce the letter c as opposed to the hard k sound, as in canard (duck).

The œ is not so much an accent as it is a ligature (a combination) of the letters o and e into a single glyph. It is pronounced the same as in the French consecutive letter pairing eu which sounds like the oo in the English words book and took. When oe occurs without the ligature, it is pronounced just as oi is in moi (me) and toi (you).

Fait intéressant: In French, œ is called e dans l’o, which literally means e in the o. Due to French pronunciation, it sounds similar to the phrase (des) œufs dans l’eau, meaning eggs in the water. This is a mnemotechnic* pun used when first learning the ligature in primary school.

*Mnemotechny is the study or practice of improving one’s memory.

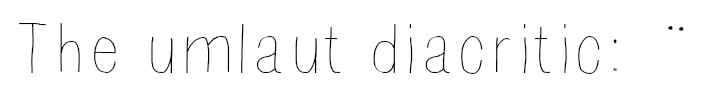

In French, the umlaut is placed over a vowel when it is to be pronounced separately from the preceding letter. On several occasions, you’ll notice that a pairing of vowels in French is pronounced as a single sound. Take mais for example; it means but, and it is monosyllabic. But if you add an umlaut above the i, making it into maïs, its meaning changes to corn, and you must pronounce the vowels separately.

The umlaut is also placed over the letters e and u to denote a pronunciation change when the otherwise silent e follows gu. Compare the French words figue, meaning fig (which shares its English counterpart’s pronunciation), and ciguë, meaning hemlock. The latter is disyllabic due to the added umlaut, and is pronounced sig-y, as opposed to sig.

Hopefully this in-depth look at the phonetics of the French language is helpful to you. Maybe you never cared about the accents or their respective uses; that’s fine. Maybe you feel like your time was wasted in reading this. That’s fine, too. I’m not hurt by that…

![cuteness-overload-rage-face[1]](https://wordsmitht.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/cuteness-overload-rage-face1.png?w=300&h=298)

But if you’re like me, and you need to learn every single tidbit of information about the language you’re learning and its history, then maybe you found this informative. I hope that’s the case. 🙂

P.S. You may have read in my very first post that I’d been planning to attach a French translation to each entry here on Wordsmith. You may have also noticed that that hasn’t been the case for most of my posts since then. I’ve decided that’s no longer something I’m going to do. Some posts end up being thousands of words long, and the translation takes me an awfully long time, as I’m still in the early stages of developing my French tongue. I may write bilingually in the future once I become more proficient. But for now, since I’m only a novice, and for the sake of saving time and space, 95% of my posts will be in English only. A few here and there may include a French translation, if I’m feeling ambitious. I hope you understand.

Also, a huge thank-you to the 50+ followers I’ve amassed so far. I really appreciate you coming along on this journey of creative writing, language, and occasional ranting and raving with me. It means a lot, and you’re all the reason I do what I do.

Write on.

French is a beautiful and romantic language, and I am enjoying every minute I spend studying and practicing it. As with any new language, however, I’m having some difficulties. I guess I shouldn’t complain, since my native tongue is English, and English is one of the most difficult language to learn. It’s got all kinds of inconsistent rules, the pronunciation of the vowels varies depending on the word, some letters are contextually pronounced as others, etc.

Back to my point. I’m struggling to understand certain rules in French, insofar as when to use different forms of the same word. I’m using a fantastic app called Duolingo which allows anyone to learn a new language, free of charge. It’s very good about explaining when to use what. But sometimes, it leaves me hanging.

Par exemple:

The words eux and les both mean ‘them.’ But are they interchangeable? If not, when do I use which word? I’ve tried scouring Google for answers, but the results are explained confusingly and are unhelpful. I’ve also occasionally seen leur, which means ‘their,’ used to mean ‘them.’ Did I make that up? Or is it really a thing?

The phrase ce sont eux qui dirigent translates into ‘they are the ones driving.’ (Literally: it is them who drive.) Could I use les in place of eux here? Why or why not? My theory is that les refers to inanimate objects, whereas eux is in regards to people or animals. Is this at all true?

Un autre exemple:

Nous is the formal word for ‘we’/’us.’ I’m familiar with the conjugation for this form. However, on is the informal version. Sometimes, I’m caught off-guard by its usage. It seems to me that the conjugation of on is the same as the conjugation of the forms il/elle. Is this correct? (i.e. nous allons = ‘we go’; on va/il va = ‘we go,’ ‘he goes.’)

These two examples are what stump me the most in French. There are others, and as I come across them again in my studies, I will post addendums to request more help. Any and all feedback is greatly appreciated!

Self Empowerment & Business Coaching

Observations from the trenches....

Paris, Travel and Family

Trivial views on significant issues

A place where you can be human.

Documenting my 2019 thru-hike attempt of the Appalachian Trail

Pen to paper

We exist to help people understand themselves.

longement apprendre français